Beechcraft Bonanza V35B & Piper PA-28 - Mid Air Collision

The Beechcraft V35B Bonanza was in a shallow climb, heading southbound, in the vicinity of Warrenton, Virginia. The aircraft was operated under visual flight rules with the pilot under the supervision of an onboard instructor. The Piper PA-28 was in level flight, also under visual flight rules, and was heading in a southeasterly direction. The aircraft collided approximately 1800 feet above sea level. The Beechcraft broke up in flight, and the pilot and flight instructor were fatally injured. There was a post-impact fire at the Beechcraft accident site. The pilot of the Piper, who was the sole occupant of the aircraft, conducted a forced landing in a pasture, approximately 6 nautical miles south of the Warrenton-Fauquier Airport. The pilot sustained minor injuries.

The Piper was registered to a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) employee, and the Beechcraft was registered to a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) employee. Given the unique circumstances surrounding the ownership and operation of the accident aircraft, the United States government requested the Canadian Transportation Safety Board to investigate as an unbiased investigative authority.

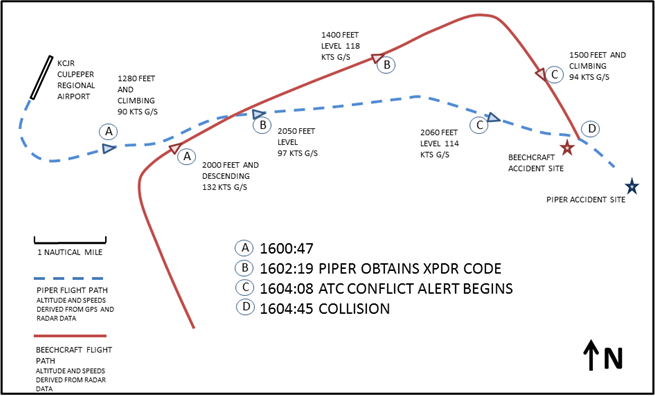

With the certified flight instructor on board, the Beechcraft departed from the Warrenton, Virginia Airport at 1545. The aircraft headed south, and climbed to 3000 feet ASL. No en route air traffic services were requested by the pilots of the Beechcraft, nor were they required to do so in the airspace in which they were operating. The recorded radar data indicated that the Beechcraft was transmitting on transponder code 1200.

At 1555, the now northbound Beechcraft was 13 nm south of the Culpeper Regional Airport at 3000 feet ASL. At this time, the Piper PA-28-140 departed the Culpeper Airport under VFR and was climbing eastward. At 1600, the Beechcraft started a descent. As the Beechcraft descended, their converging point of approach was 600 feet vertical and 0.9 nm lateral.

It is not known if either pilot saw the other aircraft, or if the 2 aircraft were on the same radio frequency.

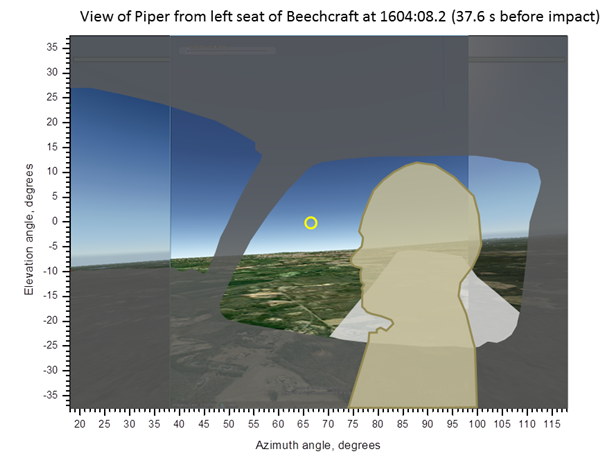

The Piper and the Beechcraft collided on a 45° convergent path from the Piper’s left side. Field-of-view analysis showed that there was a high likelihood that each aircraft was visible to the other, meaning that no aircraft structure would have obscured the view of either approaching aircraft. The Beechcraft pilot’s view may have been obscured by the instructor’s head, depending on each pilot’s seat position and posture, but the instructor’s view would have been unobstructed. There were no indications that either aircraft maneuvered to avoid the other.

As the 2 aircraft collided, the Piper’s propeller severed the Beechcraft’s fuselage just aft of the pilots’ seats. Without the empennage and ruddervators attached, the Beechcraft’s cockpit and wings entered a dive, resulting in an impact that was not survivable and a post-impact fire. The right ruddervator and aft portion of the empennage/tail cone of the Beechcraft remained embedded in the Piper’s fuselage. The Piper’s engine failed, and there was a loss of airspeed indication. The pilot then completed a successful forced landing into a pasture.

Good visual meteorological conditions were reported in the Warrenton area.

Neither aircraft was equipped, nor was required by regulation to be equipped, with any form of aircraft collision avoidance technology.

Both aircraft were visible on radar at the Potomac TRACON ATC facility. The controller on duty received a system automated collision alert but assessed the risk of a collision between the two aircraft as insignificant. The controller was also distracted at the time by providing separation between IFR aircraft in the sector. No alert was raised by the control and no conflict information was given to the two occurrence aircraft.

The only preventative measure which was left to these two pilots was the VFR method known as “See and Avoid”. Neither pilot saw the other aircraft in time to avert a mid-air collision, likely due to the inherent limitations of the “See and Avoid” principle. This principle is only effective if both pilots maintain a constant lookout for conflicting traffic.