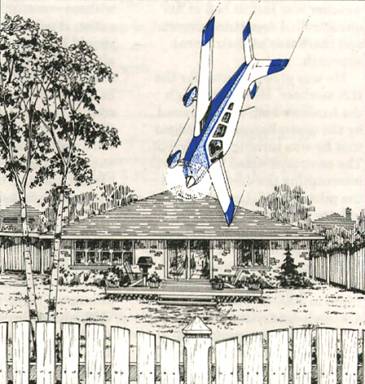

Fatal Accident Near St. Andrews, Manitoba

The investigation by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) into the fatal aircraft accident near St. Andrews, Manitoba, on July 11, 1999, is continuing. The following is an excerpt of TSB press release A 15/99.

On the day of the accident, a number of private aircraft were being used to give Girl Guides and Girl Guide leaders, involved in a nearby Girl Guide Jamboree, familiarization flights in the vicinity of Birds Hill Park, Manitoba. One of the aircraft being used for the flights, a privately registered Mooney M20F, departed St. Andrews Airport around 11:20 Central Daylight Time (CDT) with a pilot and three Girl Guide leaders on board.

Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft was seen to enter an abrupt left roll and enter a spin. The aircraft crashed into a residential acreage, about 75 ft. from a house. The pilot and two passengers were fatally injured on impact; the third passenger died en route to the hospital.

TSB investigators attended the site and removed the aircraft to a hangar at St. Andrews Airport for detailed examination. Water was found in several areas of the aircraft's fuel system. Corrosion was found in the engine-driven fuel pump and in the fuel filter. The significance of the water and the corrosion has not been determined. A detailed examination of other components of the aircraft's fuel system is underway. There were no anomalies found with the aircraft's flight control systems.

The engine was removed from the aircraft and taken for detailed examination at the TSB regional facility in Winnipeg. Impact damage to the engine precluded a test run, but a thorough examination of the engine and its components showed no pre-impact damage.

The aircraft was equipped with a stall warning system designed to activate if the aircraft approaches an aerodynamic stall. The stall warning horn was removed from the aircraft and also tested at the TSB regional facility. The steady tone produced by the horn during the test was similar to the steady tone recorded on the St. Andrews tower tape during the last radio transmission made by the pilot. The last radio transmission was confined to the establishment of communication with the St. Andrews tower. The tape has been sent to the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa for further analysis.

Air traffic control (ATC) radar tapes have been reviewed. The aircraft was equipped with a transponder; transponder transmissions from the aircraft were recorded on the ATC radar tapes. The recorded transmissions indicate that the aircraft reached an altitude of 1100 ft. above sea level, or 340 ft. above ground level, approximately 45 seconds after takeoff; the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) was heard about 10 seconds later. The TSB will issue a report upon completion of its investigation.

Take Five - Winter Tips

Winter brings changeable weather with fast-moving fronts, strong and gusty winds, blowing and drifting snow, and icing.

This calls for good judgment, caution, changing some habits, and caring for your aircraft.

So much for the generalities; let's get down to specifics.

Winter Care

- Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for winterizing.

- Use recommended baffling and covers.

- Check all hoses, flexible tubing, and seals for the signs of deterioration: cracks, hardening and lumps. Tighten loose clamps and fittings.

- Adjust control cables to compensate for cold contraction.

- Remove wheel covers to reduce the chance of frozen slush locking the wheels and brakes.

- Inspect the heater system for leaks (carbon monoxide).

- Use covers for at least the pitot, engine and wings if your aircraft is parked outdoors.

- Top up the fuel after landing - this will reduce condensation icing in the fuel system.

- Keep the battery charged, or remove it if your aircraft is parked outside. (Take the same care of the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) battery. If you need it, you’ll want it to perform properly.)

Be Weather Wise

- Winter weather is not more hazardous; it's just different - and a trifle unforgiving.

- Plan carefully.(Do you really understand that forecast? Have you prepared alternate ways out in case you run into a problem or unexpected weather? Have you allowed for the shorter day?)

- Carry a safe margin of fuel for any change in plans.

- File a flight plan or itinerary, and forward any amendments to air traffic control.

- Dress for the weather outside the cockpit. (You could have heater failure, or even an emergency landing).

- Monitor weather broadcasts, request PIREPS (and give them), and get forecast updates en route.

- Watch for the warning signs of weather ahead: clouds, indefinite horizon, wind and temperature changes, and cars using headlights during the day (blowing surface snow).

- Know what a whiteout is, especially if you fly over large frozen lakes or snow-covered terrain with no contrasting features. It happens when snow-covered, featureless terrain blends into an overcast sky: the horizon disappears, disorientation sets in quickly and height perception is lost. Can you handle instrument flight?

- Be alert for carburetor icing around the freezing mark.

- Warm the engine periodically during low-power descents and approaches.

- Set reasonable limits and stick to them; otherwise you could be tempted into pressing on.

Pre-Flight Additions

- Make sure the oil breather tubes are ice-free.

- Drain enough fuel for a proper contamination check (if it doesn’t drain freely, suspect ice in the line or sump).

- Clear the pitot tube, heater intake, fuel vents, and carburetor intake of snow or ice.

- Make sure the gear is ice-free.

- Clear ice, snow and frost from lift and control surfaces. (Even a little frost can destroy lift!)

- Bring adequate survival gear.

- Check the ELT transmission.

- Make sure the ski safety cables and shock cords are in place.

- Preheat the engine and cockpit, if possible.

- Follow oil dilute directions, if equipped.

Carbon Monoxide

Don’t count on fumes from a leaky heater to warn you of carbon monoxide. Here are some of the symptoms: sluggishness, warmth, tightness across the forehead and headaches, ringing in the ears, nausea, dizziness, and dimming of vision. If any of these occur, shut off the cabin heat, open a fresh air source, don’t smoke (it will aggravate your condition), use 100 percent oxygen if available, and land as soon as possible.

Scary Checklist, eh? Well, it’s just a summary of what has happened to others. Keep this handy, and you’ll go places — all the way!

The PA-31 flight had been relatively routine except for the turbulence — occasional moderate and several tense minutes of severe turbulence. But aside from being a little shaken, everybody was OK.

It was several days later when the AME discovered the damage during a routine maintenance check: distorted exhaust shield assembly, distorted leading edge nacelle plate and both inboard and outboard nacelle skin. Further investigation revealed numerous sheared and loose rivets under the skin between the shear plate and the engine-mount bracket, and other sections of skin.

It was only after questioning the pilots that the AME learned of the severe turbulence encounter. It was fortunate that the damage had not been more extensive.

Severe turbulence is defined in the A.I.P. MET 3.7 section as: "Turbulence in which the aircraft is violently tossed about and is impossible to control. It may cause structural damage" (emphasis added by the editor).

Not only should turbulence reports be filed with ATC to inform other pilots, the encounter should also be reported to your AME so that he/she can verify that the aircraft is still airworthy for others to fly.

Originally Published: ASL 4/1996

Original Article: Reporting Turbulence Encounters

Good Judgement Overruled

There are times when you just don't take off. There is no question about it, no thought needed, when, for example, the weather is totally outrageous, the airplane is not really airworthy or some other problem exists that makes [the] proposed flight just downright dangerous. Every pilot is confronted with such circumstances every so often. There is little doubt about what could happen if the airplane leaves the ground that day.

Brian Jacobson corporate pilot and Contributing Editor to Aviation Safety magazine

One pilot's reason for departing VFR into instrument meteorological conditions was that he needed to get his Piper Archer from airport A to airport B 14 mi. away to have it repaired so that he could leave for Florida the next morning.

He had had a total electrical failure the previous day while practising instrument approaches with a friend. He was recharging the battery but needed to get his alternator repaired. The problem was that the weather was solid IFR.

When he called the FSS that morning for a weather briefing, he explained to the specialist that, while he held an IFR rating (having 600 hrs' total time, of which 60 hrs were instrument time and 370 hrs were on type), he could not file an instrument flight plan because of his electrical problem. If he were flying VFR, he could use battery power for his radio and transponder to enter the Class C airspace at airport B.

The weather at B was 300 ft. overcast, with visibility 0.75 mi. in light rain, and forecast to stay that way until evening. The briefer told the pilot that VFR was not recommended.

The pilot explained that he needed to get to B for repairs since he was leaving early the next morning for Florida. "Well, the thing is, if I could fly there IFR... but it's just not legal for me to do that, you see, with only the battery working."

"The alternator is completely out, and I don't know how long the battery is going to last, much less if I'll get the airplane started."

"I guess I'll check with you again, maybe around noon. When will this be updated?"

The pilot's urgency was evident in the conversation. When he called back, he repeated his story about the alternator failure and the need to fly VFR to B for repairs. The updated forecast for B called for 500 ft. overcast and visibility 2 mi. for the rest of the day and evening. He told the briefer that he would be in touch with the tower at B in case the weather improved enough for him to get there.

When he called the briefer back a third time just before 5 p.m., he told much the same story, but this time, instead of saying that he needed VFR, he said, "I have to get special VFR." He had decided to go regardless of the weather.

The briefer advised him to wait until morning, when the weather would improve. The actual weather at B was 300 ft. overcast and visibility 2 mi., with the forecast not much better for the rest of the night. The pilot thanked the briefer, hung up and called the tower at B. He advised the controller of his need to get special VFR into the control zone. After confirming that he had a radio, the tower controller advised him to contact the terminal controller after takeoff to make his request.

The pilot did that just about an hour later. He was given a transponder code, identified on radar and advised that there would be a 5-min. delay because instrument approaches were in progress at B. When the clearance was given, the pilot asked for a heading to the airport. He was assigned a vector.

A Cessna 421 pilot flying the ILS approach at B overheard the conversation. When he checked in on the tower frequency, he advised that conditions on final were not conducive to special VFR. That information was passed on to the arrival controller handling the Archer.

When told that the ceiling on final at B was 300 ft., the Archer pilot replied, "Well, I guess it's too late for me to go back. So, I'll fly the approach, okay?" Since only 14 mi. separated the two airports, it is likely that the weather was just as bad at his uncontrolled departure airport, and there was no instrument approach.

He was given a vector for the ILS localizer. He flew through the localizer and, when queried by the controller, acknowledged that he was turning to intercept. The controller noted that he was intercepting the on-course and the pilot agreed. Less than a minute later, the pilot advised that he was having a gyro problem. "It's all mixed up," he said.

The controller immediately responded by telling the pilot to climb to 3000 ft. The pilot acknowledged, but added, "I'm going to lose communication pretty soon. My battery is pretty bad." The controller intended to provide a surveillance no-gyro approach and he began giving directions to turn, stating when to start the turn and when to stop. The static-filled transmission "DG not working" was the last from the aircraft. It crashed in a residential area, killing the pilot. No one on the ground was hurt.

Including the time required for engine start-up, the aircraft had been operating at power for about 30 min. when it crashed.

Investigators found no indication that the gyro was not operating normally at impact. Even without communication or navigation capability, the pilot should have been able to fly the aircraft. However, it is possible that, in the high-stress situation, he started to overcontrol the aircraft to the point where he thought that the instruments were malfunctioning. When he stopped believing and scanning his instruments, he apparently became disoriented and lost control.

A 14-mi. trip in good VFR conditions would not likely have caused any difficulties, even on questionable battery power; however, the weather for the attempted flight was not "good VFR." It had been reported at 300 ft. overcast with visibility 2 mi. most of the day. Waiting until the following morning to ferry the aircraft to airport B to get the alternator replaced would have cost the pilot a couple of hours' delay in the start of his Florida trip.

When forced by the weather to fly a full instrument approach on a fading battery, the pilot knew that he had a serious emergency, and he should have declared it. The controller knew about the aircraft's mechanical conditions, but reasonably expected the pilot to have enough battery power available to do what was expected during the flight. Since the pilot did not declare the emergency, the flight was treated in a routine manner. Had the controller known that an emergency existed, he could have assisted by turning him in early for the ILS approach or perhaps immediately giving vectors for the surveillance approach.

The accident should not have happened. It happened because the pilot convinced himself that it was acceptable to take a questionable aircraft through poor weather to save a couple of hours. His good judgement was overruled by the self-imposed pressure to get an early start the next day.

Human factors experts would call it an example of a mental "trap" known as a "framing bias."

One of the things that contributed to the poor judgement illustrated in this accident is the way that a problem is framed. In risky decision making, there is a tendency to frame the problem as a choice between gains and losses.

With respect to lossed, people are biased to chance the risky loss, which they see as less probable, although more disastrous, than the certain loss.

Think about which way your bias is!

Originally Published: ASL 4/1997

Original Article: Good Judgement Overruled