GPS Direct...Or Is It?

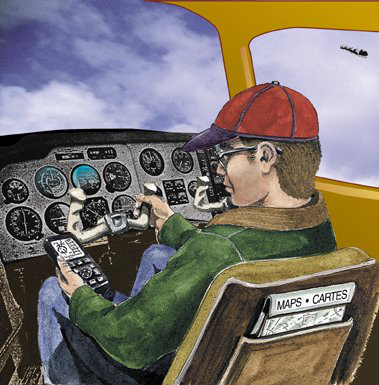

Is this the neatest toy or what?! Navigation is a piece of cake now!

The following account highlights the critical importance of maintaining proper map-reading skills and, more importantly, the need to always know your position on your visual flight rules (VFR) map even though you are flying a global positioning system (GPS) direct route.

A pilot and two passengers flew to Lac Portneuf, Quebec, in a float-equipped Cessna A185F on June 9, 1997, for a fishing trip and had planned to return home to Pittsfield, Maine, on June 13, 1997. The aircraft took off as scheduled on June 13 with a planned refuelling stop at Lac-Sébastien, 51 NM to the southwest; however, the pilot returned to Lac Portneuf because fog and low visibility prevented him from reaching his destination. The pilot delayed the departure until the next day. On June 14, the takeoff was delayed again because of fog and rain, but the pilot and his passengers eventually departed at 08:45 from Lac Portneuf on a VFR flight to Lac-Sébastien.

Around 09:30, witnesses about three miles west of Lac-Morin heard the sound of an aircraft engine pass overhead, soon followed by a sound of impact. They did not see the aircraft because the visibility was restricted by thick fog. The aircraft did not arrive at its destination as scheduled on the flight plan, and searches were undertaken. It was found at about 13:30 on the same day. It crashed at the 2500-ft. level of the east side of a mountain that rises to 2650 ft. above sea level (ASL) in straight-and-level flight on a magnetic heading of 250°. The aircraft was destroyed and the three occupants were killed. This synopsis is based on Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) Final Report A97Q0118.

The pilot and both passengers were wearing seat belts but these gave way under the force of the impact, and the three occupants were thrown from the aircraft. The pilot was certified and qualified to fly day VFR only. The TSB determined that the installation of the floats was not documented in the aircraft's technical log books, as required by regulation. The aircraft was properly equipped for instrument flying. Further, it was fitted with an autopilot that kept the wings level and with a GPS navigation receiver. This navigation system is more efficient than traditional means of navigation and therefore reduces the pilot's workload.

The GPS installed in this aircraft displays the aircraft's geographical position, ground speed, time of arrival, distance, and track to programmed locations; it does not display ground elevation. The GPS receiver in the aircraft would indicate the bearing and distance to the destination at all times no matter where on earth the aircraft was physically located. Pilots tend to rely on this information and do not have to attend to where the aircraft is geographically located because they know they are not lost and they can always fly directly to their destination. The aircraft had no radio altimeter or ground proximity warning system, nor was either required by regulation.

An emergency locator transmitter (ELT) was installed and in working order, but the signal was not received by any aircraft or the Search and Rescue Satellite Aided Tracking (SARSAT) system because the antenna broke off on impact. About 08:00 on the day of the accident, the pilot observed a commercial aircraft flying southwest, so he telephoned a Lac-Sébastien aircraft operator to obtain current meteorological information at his destination. He was informed that conditions were favourable for visual flight, and that the ceiling was 2000 ft. ASL. At 08:20, the pilot submitted a VFR flight plan and he was to leave Lac Portneuf at 08:45 and proceed direct to Lac-Sébastien at an altitude of 2500 ft. ASL. According to the flight plan, the flight time was 45 min, with an endurance of 2 hrs. The chosen route was over a heavily wooded area with lakes, mountains and valleys; the elevation of the summits ranged between 2000 and 2900 ft. ASL. The pilot did not request or receive any weather information relating to the planned route from the FSS.

Conditions at Lac Portneuf were favourable for VFR flight on takeoff. In the area where the accident occurred, visibility was very restricted or almost zero in fog. At the time of the crash, a bush pilot who knew the area well reported that the peaks of the mountains were concealed by clouds. Four hours after the accident, the pilot of the search and rescue (SAR) helicopter observed localized low clouds in the area of the accident.

The east side of the mountain where the aircraft crashed has a steep slope and is densely wooded. The seaplane hit the ground, and then a rock face, in a slightly nose-up attitude with 5° of left bank. The wings broke off at impact and the cabin was heavily damaged. Examination of the engine and the propeller at the site suggest that the engine was turning on impact; however, the examination could not determine the power that it was producing. There was no evidence suggesting that the aircraft had suffered a structural failure, flight control problems, electrical problems, power loss, or that fire broke out during flight.

A controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accident is when an airworthy aircraft inadvertently strikes the terrain or water without the crew's suspecting the tragedy is about to happen. According to CFIT accident statistics collected by the TSB, pilots often tried to see the ground to fly VFR even though the flight was taking place in clouds, at night, in whiteout, or in other conditions that did not permit visual flight. More than half of such CFIT accidents occurred in VFR flight. In 1995, the TSB recommended that Transport Canada (TC) initiate a national safety awareness program addressing the operational limitations and safe use of GPS in remote operations. TC issued several special aviation notices since, which detailed the use of GPS in Canadian airspace, and also published a number of articles on GPS in recent issues of the Aviation Safety Letter.

Analysis - The prevailing weather conditions at the points of departure and arrival were favourable for visual flight, but the pilot could not have known that local conditions along the way were poor, as the area is largely uninhabited and weather information was not available. Faced with deteriorating weather conditions, which made continuation of the flight hazardous, the pilot had to make a decision either to find a suitable lake for landing or to make a diversion. The pilot decided not to land, but to deviate from the direct route and try to reach his destination by veering southeast in order to fly in visual meteorological conditions (VMC).

It is likely that the pilot was not aware of his true position in relation to the terrain and topography of the area and was relying on the GPS to get to his destination because the weather conditions required him to focus the greatest part of his attention on manoeuvring the aircraft to maintain VMC. In low-altitude flight, the pilot would have difficulty following his progress on the VFR navigation chart, on which the elevation of the terrain appeared. Consequently, although the pilot knew where Lac-Sébastien was located in relation to his aircraft, he did not know his exact position and was flying at an altitude lower than some of the surrounding terrain.

The TSB could not determine why the pilot decided to continue the flight in adverse conditions, but it is likely that the nearness of the destination and the pilot's reliance on the GPS had an influence on his decision. The desire of the pilot and the passengers to return home after the first delay may have influenced the pilot's decision to undertake the flight.

In the end, the TSB determined that the pilot continued his flight in adverse weather conditions and probably did not have the necessary visual references to avoid hitting the steep slope of the mountain. Likely contributing to this occurrence was the pilot's reliance on GPS instead of the navigation chart while attempting to maintain VMC.