Underwater Egress — Revisited

The following accident represents a nightmare for all pilots (what accident doesn’t?), but particularly for seaplane pilots. It was the subject of "Learning From Others," an excellent letter from a reader in Aviation Safety Letter 2/97, but the recent release of Transportation Safety Board (TSB) Final Report A96Q0114 gave us no alternative but to highlight this tragic accident before the summer of 1998 arrives. We will also address specific issues relating to the aft emergency exit on the Cessna 206 series floatplane and emergency egress from an inverted, water-filled aircraft. The following has been condensed from information contained in the TSB Final Report, which is available on the TSB’s Web site http://www.tsb.gc.ca/.

On July 20, 1996, the float-equipped Cessna U206F with six persons on board started its takeoff run on Rivière des Prairies, Quebec, on a water surface agitated by strong crosswinds from the right. The aircraft lifted out of the water at very low speed, travelled about 1000 ft. before taking off, and fell back on the water in a pronounced nose-up attitude. The pilot continued with the takeoff, and the aircraft lifted out of the water a second time. The left wing then struck the surface of the water, the left float dug into the water, and the aircraft capsized. The pilot told the passengers to unfasten their seatbelts as the aircraft rapidly filled with water. He then went toward the rear to try to open the two cargo doors to let the occupants out. A witness immediately proceeded to the site to assist the occupants. He opened the left front door, and the female passenger and her child evacuated the seaplane. As they had no life jackets, these two persons clung to the floats until the other rescuers arrived. The first firefighters and police officers arrived at the site about 15 min after the accident. The pilot and the other three passengers had drowned inside the aircraft.

The TSB determined that the pilot had been unable to maintain control of the aircraft, which was equipped with Robertson and Flint Aero kits, during a takeoff with 20° of flap in strong crosswind conditions. It also determined that the distribution of the passengers and the complexity of opening the leaves of the rear cargo door with the flaps extended to 20° contributed to the difficulty of the evacuation. There are several issues worth looking into here, but we will limit our discussion to two main areas: (1) the pilot’s decision-making process before and during the short flight, and (2) the aft emergency exit of the Cessna 206 and emergency egress from a water-filled, inverted aircraft.

The facts as provided in the TSB Report would lead many to question why this flight was attempted. Unfortunately, we will never know for sure what led the pilot to go ahead with it. Some would postpone a pleasure flight in a seaplane with three children on board when faced with strong crosswinds and agitated waves, but it often becomes a personal judgement call; it can be assumed that other experienced seaplane pilots might also have decided that the conditions at the time were acceptable. In any event, the pilot was obviously confident in his ability to handle the crosswind; perhaps the fact that the aircraft was equipped with a short takeoff and landing kit and auxiliary wing-tip tank kit, which increase lift and reduce the stall speed of the aircraft, reinforced his confidence.

The second question mark arises from the fact that, during the initial takeoff, the aircraft fell back on the water in a pronounced nose-up attitude, but the pilot decided to continue with the takeoff. The only answers to these questions reside in the complex world of human factors, as they apply to the pilot’s own motivations and self-imposed pressures to go ahead with the flight. As stated in the ASL 2/97 article, remember this particular occurrence the next time that you are faced with similar circumstances.

Emergency Exit

A second fatal accident in less than 12 months brought the issue of the Cessna 206 emergency exit to the forefront. On June 1, 1997, a U.S.-registered float-equipped Cessna 206 had a similar accident at Carroll Lake, Ontario, when the aircraft nosed over in the water, and two passengers were unable to evacuate the aircraft and drowned (TSB A97C0090). In this particular case, the pilot had left the wheels down when he touched down on the water.

The Cessna 206 is equipped with a double cargo door on the right rear side that doubles as an emergency exit. When the flaps are extended to 20°, the forward leaf of the cargo door can open only about 8 cm, and this makes it difficult to fully open the aft leaf of the cargo door. The emergency-exit instructions found in the owner’s manual say that, if it is necessary to use the cargo doors as an emergency exit and the wing flaps are extended, the doors are to be opened in accordance with the instructions shown on the red placard mounted on the forward cargo door. According to the TSB Final Report, the instructions found on the placard of the accident aircraft were as follows:

Emergency exit operation:

- Rotate forward cargodoor handle full forward then full aft.

- Open forward cargo door as far as possible.

- Rotate red lever in rear cargo door forward.

- Force rear cargo door full open.

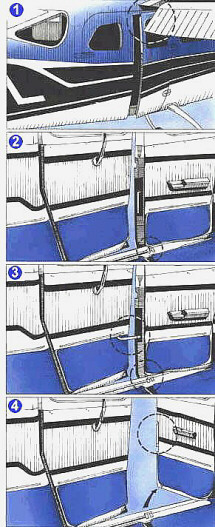

In ASL 7/90, as a result of a safety information letter from the Canadian Aviation Safety Board, we showed the correct procedure for opening the doors with the flaps down. The procedure is repeated below, along with the original graphic, which clearly illustrates the difficulty:

(a) unlatch the forward cargo door;

(b) open the forward cargo door as much as possible (about 3 in.) (figures 1 and 2);

(c) unlatch the rear cargo door by pulling down on the red handle (figure 2);

(d) partially open the rear door until the door latch at the base of the door is clear of the floor (figure 3);

(e) close the rear cargo door latch by placing the red handle into the well in the door jamb (the locking pins will now be extended, but clear of the fuselage); and

(f) push open the rear cargo door (figure 4).

This sequence shows that the placard leaves out some of the above steps. Now this procedure is quite demanding for most people under normal circumstances. Picture the process in the dark, in an inverted airplane, in rushing water and with two or three distressed passengers trying to escape.

The Cessna 206 emergency-exit issue has been addressed extensively in the past by, among others, the TSB in 1985 and 1989; the ASL 7/90 article referred to above; Cessna service bulletin (SB) SEB91-04, issued on March 22, 1991; and many letters exchanged among the industry, Transport Canada (TC), the TSB and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) since the last two fatal accidents. In addition, you — the owners, operators and associations — are well aware of the problem. Although the SB simplifies somewhat the steps required to open the double aft cargo door, the procedure does not eliminate the jamming of the forward cargo door against the flaps when they are lowered. TC clearly stated to the FAA its position that, even with the modification, when the flaps are down, the Cessna 206 emergency exit procedure remains a multistep procedure that can be difficult to execute under emergency conditions.

Following the Carroll Lake occurrence, TC reiterated its concerns to the FAA, and, in its November 1997 reply, the FAA said that new series 206H and T206H would incorporate the provisions of SEB91-04. The FAA also said that, if TC were to issue an airworthiness directive (AD) against 206 series airplanes, the FAA would examine it for possible similar action in the United States. However, owing to the proportionally wider use of floatplanes in Canada than in the United States, the FAA could not say at that time whether an AD with the same intent would be supported by the evidence available from its U.S. databases.

Meanwhile, on November 16, 1997, TC issued Service Difficulty Alert AL-97-04, which strongly recommends that owners and operators of all Cessna 206, U206 and TU206 aircraft incorporate SB SEB91-04; instruct flight crews to brief passengers and demonstrate the steps necessary to open the exit when flaps are lowered; and ensure that flight crews periodically practice the procedure for opening the emergency exit from outside the aircraft when the flaps are down. It also recommends that there be a maximum of four occupants in the aircraft when waterborne operations are being conducted.

At this time, there is no modification available that completely resolves the emergency-exit issue. Discussions are still ongoing among TC, the FAA and the industry about the possibility of AD action.

Underwater Egress

The TSB’s final report refers to a study relating to escape and survival from a ditched aircraft. It states that the rotation of the body underwater and loss of gravitational reference makes disorientation inevitable for survivors prior to their escape from an inverted aircraft. In addition, the darkness produced by water flooding into the aircraft aggravates the disorientation. Survivors who were questioned in this study reported having experienced confusion, panic and disorientation in the occurrences. The study concludes that only those who have experienced disorientation in an underwater trainer understand the problem and know how to deal with it to get out and survive.

Having personally experienced an underwater escape trainer twice, I can attest to the fact that the above statements reflect the reality of an underwater egress situation, except that, in the trainer, you expect the situation to arise (there is no surprise effect); you have a plan or escape route in your mind (or at least you think that you do...); and you are in a clean pool with safety scuba divers. Not so in the real world. Nevertheless, underwater egress training is invaluable for any pilot who flies regularly over water, regardless of the type of aircraft flown. As a matter of fact, passengers or non-pilot crews who also fly regularly over water should consider underwater escape training. Once you have had the training, you will also be in a better position to brief your passengers about what to expect... should the unexpected occur.

Finally, ASL 2/95 featured "Seaplane Accident Survival" as its lead article, and it contained excellent information on this subject. If you do not have a copy of that article, we will be pleased to send you one upon request.

Originally Published: Aviation Safety Letter 02/1998

Original Article: Underwater Egress - Revisited

From Issue 1/92

Company Aviation Safety Management

Immediately after an aircraft crashes, accident investigators launch into a concentrated search for cause factors. Their sole objective is to identify the cause and communicate it to the aviation industry in an attempt to reduce the chances of a repeat performance by another operator. Fortunately, many aircraft operators benefit from this approach to accident prevention, but, regrettably, someone always has to have paid the supreme price. You cannot just rely on learning from the mistakes of others ¾ it's too much of a sacrifice for them!

In the majority of cases, accidents happen as a result of an unbroken chain of events that ultimately results in total system failure, but these events that form the chain can be controlled. As soon as the sequence of events is positively altered, the chain is broken and the accident prevented and reported as an incident with accident potential.

Breaking the chain is a challenge that all aircraft operators are confronted with. Some do it systematically and very effectively. Others do it by trial and error. The latter method very often costs lives and money in large amounts.

We believe that successful operators function efficiently and safety because of their Company Aviation Safety Management Program. With an effective program in place, accident chains rarely form. And in cases where they do begin to form, they are broken after the second or third link.

It does not matter how large or small an operation is. It could be one single-engined aircraft or a complex fleet of wide-bodied jet transports. The principles of aviation safety management are applicable to either and all of those in between.

Responsibility for safety always has to start at the top and work down through the various levels of management to the bottom rung.

Safety management requires professionalism, integrity and two-way communication. With effective communication and responsible attitudes, safety deficiencies are identified, reported and eliminated. To identify deficiencies, which are actually links of the accident chain, most operators require a dedicated safety officer to act as an advisor to the chief executive officer, a safety committee and a reporting mechanism so that all employees can assist in the identification of system flaws.

In the case of a one-person operation, the individual has to wear all the hats but still apply the basic principles of monitoring, identifying and acting to eliminate system deficiencies and reduce the accident potential.

We believe that our accident-prevention program offers a solution for establishing effective safety management.

The Directorate of System Safety staff in all of our regions provides guidance, courses and workshops on Company Aviation Safety Management to the Canadian aviation industry without cost.

If you do not have a safety program tailored to your needs, call on your Regional Aviation Safety Officer for assistance. Click here to view the list of regional offices.

Try it — you might like it!

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 1/92 - Company Aviation Safety Management

From Issue 6/87

Pilot Decision Making and Safety

If you've decided to actively participate in the Pilot Decision Making workshops now being conducted by your Regional Aviation Safety Officer, you've already made a significant personal contribution towards the promotion of aviation safety in Canada. We hope that you'll attend and share your concerns at all of the PDM safety sessions being offered in your area.

If you're undecided about participating, contact your RASO and ask for more information about decision-making training and what it can do for you.

The program is very dependent on your participation. By sharing some of your thoughts and concerns, others will benefit from your experiences. Of course, you'll gain too by listening and analysing the thoughts and concerns of other pilots.

The workshops being presented across the country by aviation safety specialists were developed by an international group of experienced pilots and aviation psychologists. Although decision-making concepts might appear to be complex, the workshop materials are presented in language that pilots understand.

You'll benefit by discussing successful flight scenarios resulting from correct decisions as well as learn from the fatal mistakes of others that resulted from either wrong or no decisions. The sessions will help you identify risk, stress and negative attitudes and teach judgment and decision-making concepts. Some of the concepts may be new to you. If not, hearing them again will jog your memory. We recommend that you give Pilot Decision Making a shot. Who knows — the life you save may be your own.

You wake up in the morning, your brain clicks on and you have to start making decisions. Do you work? Do you play? What do you wear? What do you eat? If you're a flyer, you'll be deciding from preflight to post-flight. Are you prepared for it? Are you rested? Are you current? Can you handle it? Do you have a system to exercise sound judgment to assist you in completing a flight safely and efficiently?

Canadian aviation accident stats continue to reveal that too high a percentage of cause factors relate to judgment and decision making.

The following examples from a recent stack of Canadian Aviation Safety Board Aviation Occurrence Reports support that finding.

A Cessna A188B pilot decided to attempt a takeoff from a 16 ft.-wide dirt road. With ditches on either side, there was no margin for error. He lost directional control and ran the aircraft into the ditch on the left side, causing substantial damage.

The first poor decision was landing there. The second and costly one was attempting to take off.

A Piper PA31-310 Navajo pilot attempted a cargo flight with three scheduled delivery stops. During the deliveries, the aircraft wasn't refuelled or even shut down at the last two stops. Enroute after the last delivery, both engines stopped. The aircraft was landed wheels up in a ploughed f ield. Damage was extensive.

The pilot admitted that he didn't compute fuel requirements and stated that he was anxious to get home because his wife was ill in the hospital.

Being preoccupied and stressed can have a disastrous effect on decision-making processes.

Although the pilot of a Lake LA4-200 was not instrument rated and most of his recent flying had been day VFR flights, he decided to depart from a remote site in marginal weather at night. Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft impacted the ice of a lake at high speed. The pilot and passenger were killed. The decision for the night departure in snow showers was the wrong one for the day VFR operator.

After starting the Piper PA-28-140, the pilot went to lunch and left the aircraft engine idling for 20 min. After lunch, he noticed that the aircraft was covered with hoarfrost. He removed some from the wing-root areas, but left the outer wings as they were. After a longer-than-normal takeoff roll, the aircraft became airborne but wouldn't climb. The pilot attempted to turn to avoid some trees, but the left wing struck a tree. Damage was substantial.

Two factors contributed to this accident, and both involved decision making. Wings covered with hoarfrost won't fly. Engines with fouled plugs caused by excessive idling won't produce rated power.

We can learn from the mistakes of others, but it also helps when we upgrade or refresh our judgment skills. Whether you are a veteran flyer or a rookie, we recommend attendance at the Pilot Decision Making seminars that are being offered by your Regional Aviation Safety Officers.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 6/87 - Pilot Decision Making and Safety

From Issue 1/76

Frost and Flight

When we say that we hate to tell this story, we really mean it. It's a story we've told you before but still needs retelling.

After takeoff the aircraft remained in a steep nose-high attitude. stalled, and dived into the ground. Witnesses heard the engine run erratically and it was not producing power at impact. However. more slgnificantly the aircraft was noticed minutes after the accident to be covered with a heavy layer of frost.

Medical evidence established that the pilot had experienced stress for several minutes before the impact, probably due to the feeling of doubt about his aircraft. And well he should have — the aircraft had been on the river overnight where it had accumulated a heavy layer of hoarfrost on its white wings. Further. a significant amount of ice and water was found in the fuel system. With the daily temperatures varying above and below freezing, condensation was inevitable in the half-filled tanks. The below-freezing temperatures at the time also added to risk of ice accumulation on the tailplane during takeoff.

He may have discounted the significance of the hoarfrost on his wings — if he had noticed it. In any case. it would have been an awkward job to remove it, with his high-wing aircraft sitting out on the water. But the fact remains that a wing will lose lift when the air rushing over the upper surface does not adhere firmly to its curvature. And nothing will unglue air more readily than the irregular surface created by hoarfrast or snow crust. Every year there's evidence that pilots choose to flirt with this lethal hazard.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 1/76 - Frost and Flight