From Issue 6/80

Say That You're There

The Twin Otter pilot was hopping mad. On final he finds a sander on the runway and has to circle until it's clear. On the ground, he gives hell to the flight service specialist for not clearing the runway. Who's at fault? The pilot is.

Given a letdown clearance to the uncontrolled aerodrome, the pilot was instructed to call immediately on the local mandatory frequency. He didn t call until final. There wasn't time to clear vehicles from the runway.

Many pilots have become complacent in a radar-controlled environment. They have accepted others, doing their thinking for them. They expect the same environment at non-radar-controlled airports, which just isn't available. Flying into uncontrolled aerodromes is a different world. People on the ground can't know you're there unless you tell them. Other aircraft in the area will know your intentions only if you broadcast what they are.

Mandatory frequencies for each aerodrome are published in the VFR and IFR Supplements. Use them to communicate your intentions and get the system to work for you.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 6/80 - Say That You're There

From Issue 2/78

Mothballed Aircraft

A recent US National Transportation Safety Board bulletin drew attention to the dangers of flying aircraft that have been brought out of storage. In one case an aircraft stored for 19 months hadn't been properly prepared for storage nor checked over before it was flown again. An inflight malfunction resulted and the two occupants were killed in the crash.

Proper preparation prior to and after storage could have prevented this needless accident.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 2/78 - Mothballed Aircraft

From Issue 2/78

Wake Turbulence

A 737 was climbing from flight level 310 to 350 with a 747 cruising 12 miles ahead at FL350, when the 737 encountered wingtip vortices. The 737 pilot said "moderate chop" for 45 seconds caused disturbance to articles in the passenger cabin, "annoying" the occupants.

Sometimes, wake turbulence is more than annoying — it can be dangerous. We know of a Canadian 727 which suddenly rolled 90° while climbing through the wake of a L1011 1215 miles ahead. Although the terms "wake turbulence" and all of the disturbed air behind the aircraft including the downwash from the wings which initially can be 1,500 feet per minute. In this "wake" the two wingtip vortices join within 5-20 wingspans behind the aircraft. Wingtip vortices are by far the rnost dangerous, possessing tangential speeds of 224 feet per second. Vortices can persist up to two minutes which means that they are active at 16 miles when the following aircraft is cruising at mach .8.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 2/78 - Wake Turbulence

From Issue 1/76

Frost and Flight

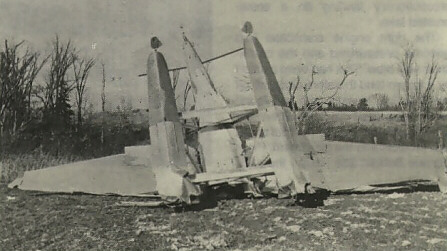

When we say that we hate to tell this story, we really mean it. It's a story we've told you before but still needs retelling.

After takeoff the aircraft remained in a steep nose-high attitude. stalled, and dived into the ground. Witnesses heard the engine run erratically and it was not producing power at impact. However. more slgnificantly the aircraft was noticed minutes after the accident to be covered with a heavy layer of frost.

Medical evidence established that the pilot had experienced stress for several minutes before the impact, probably due to the feeling of doubt about his aircraft. And well he should have — the aircraft had been on the river overnight where it had accumulated a heavy layer of hoarfrost on its white wings. Further. a significant amount of ice and water was found in the fuel system. With the daily temperatures varying above and below freezing, condensation was inevitable in the half-filled tanks. The below-freezing temperatures at the time also added to risk of ice accumulation on the tailplane during takeoff.

He may have discounted the significance of the hoarfrost on his wings — if he had noticed it. In any case. it would have been an awkward job to remove it, with his high-wing aircraft sitting out on the water. But the fact remains that a wing will lose lift when the air rushing over the upper surface does not adhere firmly to its curvature. And nothing will unglue air more readily than the irregular surface created by hoarfrast or snow crust. Every year there's evidence that pilots choose to flirt with this lethal hazard.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 1/76 - Frost and Flight